My Parents Didn’t Do Their Best, What Do I Do Now?

For some adults, their parents are not the people who love them the most.

For some adults, there comes a time when they have to face a harrowing reality: their parents are incapable or unwilling to be the people they need them to be.

For some adults, their parents are not the people who love them the most. Their parents are not their safe space. They are not the people they call in an emergency. Their parent is a source of fear rather than safety.

This realization is intensely painful because we hear messages like, “No one will love you more than your parents.” Those children often become adults who (fortunately) discover someone was able to love them way better than their parents.

There’s a level of pain, peace, and freedom that comes with realizing that your caregivers just aren’t going to be the people you were promised they would be. But what do you do after that reality becomes glaringly apparent?

Being a parent is hard. It’s stressful, and sometimes you’ll raise your voice, mess up, say the wrong thing, or forget something important. But I want every adult abused as a child to understand and accept this: Not abusing your child is very easy. If a parent abused you, you didn’t deserve it.

Bruno Bettelheim wrote the book A Good Enough Parent about parents who do not strive to be perfect and do not expect perfection from their children. Good enough parents mess up, and they make attempts to fix it. These are not the parents I am talking about in this email. This email is for those of you that have had to mourn the loss of a parent that never was a parent, the parent who is still alive but not present, and the parent who took from your life instead of adding to it.

Most adult children want to be close to their parents. They long for the relationships they see on social media and among their peers. When this isn’t possible, it’s heartbreaking. Most adults who grow up in this type of home develop self-esteem issues, have difficulty forming relationships, and struggle to trust others. Realizing that the very person(s) who was supposed to love and protect you more than anyone in the world didn’t do their job is painful.

It’s painful even if they didn’t mean to, or there are reasons to explain why this happened.

Did I Deserve It?

Absolutely not. I’ll say it again: No

I don’t care how “bad” you were as a child. I don’t care how many classes you failed or how much you “talked back.” No child deserves to be abused, and I would argue that most of your symptoms/”bad” behavior resulted from that abuse and not because of who you are.

Most of the conversations I have with adults who were abused as children revolve around the idea that they can somehow convince their parents to treat them kindly. Or things would have been different if they just changed their behavior a little bit.

Abuse (child abuse, domestic violence, etc.) often goes hand in hand with this narrative that it only happened because of something the victim did, and if they didn’t do that thing, the abuse wouldn’t have happened. This narrative gives the victim a false sense of control: if I change my behavior, this bad thing won’t happen anymore. But you quickly learn that this is a false promise. There is nothing you could have done to prevent this from happening because you were the child, and they were the adult. You did not have the power.

I want you to try repeating these statements to yourself whenever this feeling comes up:

- All children are deserving of love and respect, including me.

- I did not deserve to be treated like that.

- It’s not my fault.

- I know what happened to me.

- I am an adult, and I can keep myself safe now.

- I did nothing wrong.

- My parents' inability to treat me well does not reflect my worth.

Why Did This Happen?

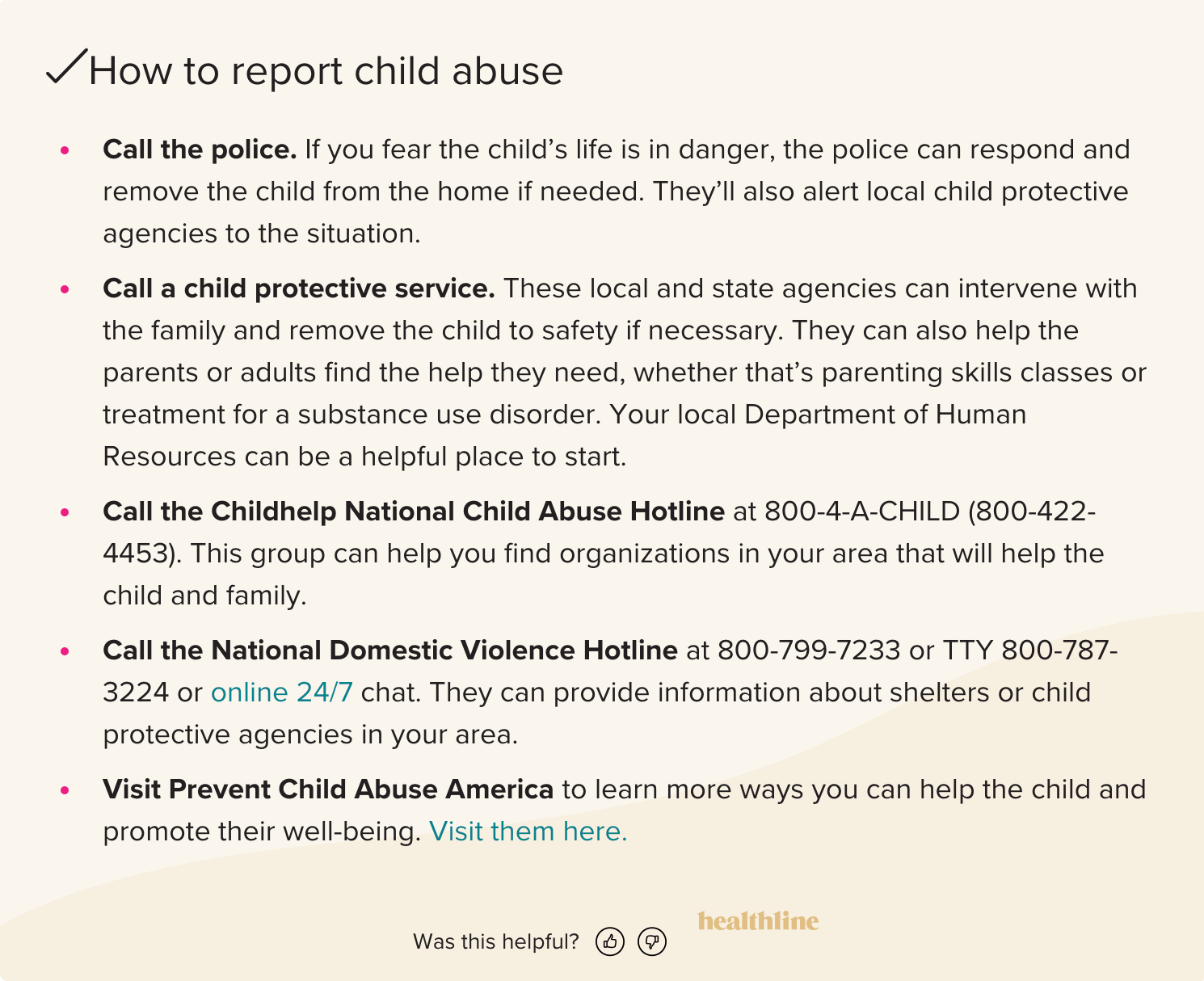

There are many reasons why child abuse may occur. Healthline outlines them nicely here.

Some parents engage in abusive behavior simply because they lack support, and it’s all they know. When some parents find support and learn new ways to parent, they’re often able to change their ways, recognize how these behaviors were not helpful, and discontinue the abuse. In cases of neglect, a lack of financial resources makes it much more likely that children will experience poor living conditions or a lack of food security, even if the parents do not want the child to have this experience. In these cases, reconciliation and a healthy relationship in adulthood is certainly possible.

In my work with abused or neglected adults, it’s not the behavior that hurts them the most. It’s the parent’s inability to acknowledge how the behavior impacted the child and their lack of accountability. There are children who experienced unfortunate circumstances that may be considered “neglectful,” but their parents were understanding, apologetic, and did not diminish the impact. As adults, we can often identify when abuse or neglect happened because of a lack of resources/support or was purposely inflicted. Many adults have lived through difficult circumstances and can reconcile this with their parents and have a productive relationship. Regardless of the intent, the impact is often the same when a caregiver cannot acknowledge and take responsibility for the outcome. When a parent can do that, it makes all the difference.

Part of the grieving process may include thinking about what you wish to hear from your parents. Some common examples are:

- I believe you.

- That shouldn’t have happened.

- I wish I had done better at the time. I know that was difficult for you.

- I should have protected you.

- I’m sorry.

- You didn’t deserve that.

If your parents can’t say these things to you, can you say them to yourself?

Making Peace With The Parents You Have

Many of you have probably been through several attempts of explaining to your caregivers why you’re upset and what you need from them. When there has been so much damage and little to no change, you may get to a point where you have to grieve the loss of the parent you wanted and accept the parent you have.

This is where I like to utilize something called Radical Acceptance. This is a DBT distress tolerance skill developed by Marsha Linehan, with ten steps. I have adapted them below to fit this type of situation.

- Recognize when you are fighting reality. This might sound like, “I wish my mom and I could be close like my friend and her mom. I wish we could shop together and go to brunch.”

- Remind yourself of the reality and what cannot be changed. “This is the mom I have. I cannot change her.”

- Address the reason for the reality: “This is just the way my mom is. It is not my fault.”

- Practice accepting this reality throughout your day.

- List all the behaviors you would change if you accepted this reality. How would your life change if you accepted who your mom is today?

- Imagine, in your mind's eye, believing what you do not want to accept and rehearse what you would do if you accepted this reality.

- Pay attention to your body sensations when you try to accept this reality.

- Allow yourself to experience the disappointment, grief, and pain that come with this acceptance.

- Acknowledge that life can be worth living even when there is pain.

- If you have trouble accepting this, look at the pros and cons of acceptance. What will happen if you don’t accept this reality?